The martians are coming

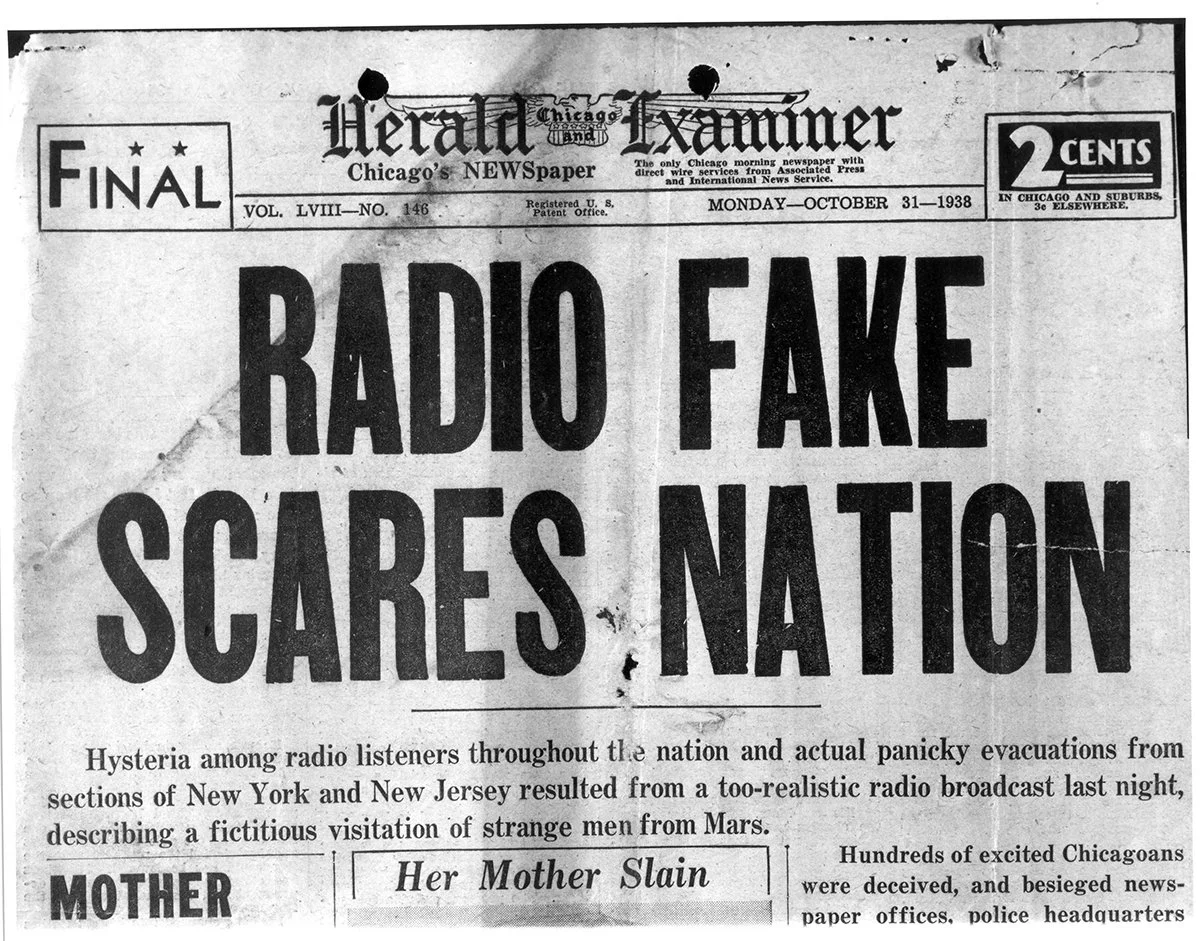

Today is the anniversary of Orson Welles’ 1938 radio broadcast of “War of the Worlds,” which offers a fascinating window into the mysteries of human psychology.

The broadcast, if you are unfamiliar, is a simulated news account of a Martian invasion. The invaders supposedly landed in New Jersey and had designs on the rest of the world from there.

It shows on one hand how sensationalized claims can be more persuasive than facts, even among people who should know better, like journalists and scientists.

There is a broadly accepted myth that “War of the Worlds” caused mass hysteria throughout the U.S. (My grandfather once explained that people were leaping to their deaths from high-rise windows rather than succumbing to the evil Martians.)

There is no evidence that is true. Welles’ Mercury Radio Theater was a high-brow, artsy show that had a very small audience. Not many people were listening and the nation’s streets were pretty quiet and peaceful that night.

Nonetheless, the story of mass hysteria quickly took on a life of its own and still persists to this day. If you say something enough times, it becomes true, whether it was true or not.

Nonetheless, clearly something was going on because police all over the country were receiving phone calls from worried citizens. Phones were ringing in Welles’ studio before the program was over, the cops showed up and threatened to arrest him, and he had to do a semi-apologetic news conference the next day. He might not have caused widespread pandemonium, but he clearly freaked out a not insignificant number of people.

If you listen carefully, it’s hard to believe anyone would fall for this, even a little. It’s hours-worth of action packed into 60 minutes, so the chronology makes no sense. Plus, there are four separate announcements that the program is a dramatization. Nevertheless…

The program creates what OZ’s Joe Plummer calls “plausible disbelief.” Welles uses the voices of fictional “experts” who have credible sounding titles and speak with authority. So, even if you don’t 100% believe it, you might not 100% disbelieve it. And those announcements about it being a dramatic performance…if you’re in the mindset of being scared, they might not fully register.

Americans were already on edge about invasion in October 1938. Germany’s takeover of Czechoslovakia and the fear of global war was the big story in the news for the previous few weeks. So, the invasion story resonated with people’s broader fears, which probably amplified the impact.

Research suggests people with low voices are more persuasive – and Welles, the main narrator, spoke with a massive baritone that rumbled like thunder.

The author David Hendy points out in Noise: A History of Human Sound & Listening that information projected aurally through a speaker via voice is more persuasive that the same material printed.

Radio is a medium that forces co-creation. Former ad executive Terry O’Reilly, host of the podcast Under the Influence, believes radio is the most difficult medium to write ad copy for – but also the most powerful, if you do it well, because listeners tell themselves so much of the story. In any medium, co-creation is powerful.

Welles later compared “War of the Worlds” to a horror movie. You’re not really believing what you’re seeing in a horror movie … but you allow yourself to get caught up in it and experience it as if it was real. And even later, upon reflection, a horror movie can stick with you and give you chills.

Brands generally don’t want to terrify people. However, there are lessons for marketers in the various unconscious factors that made “War of the Worlds” such an enduring cultural touchstone moment.